|

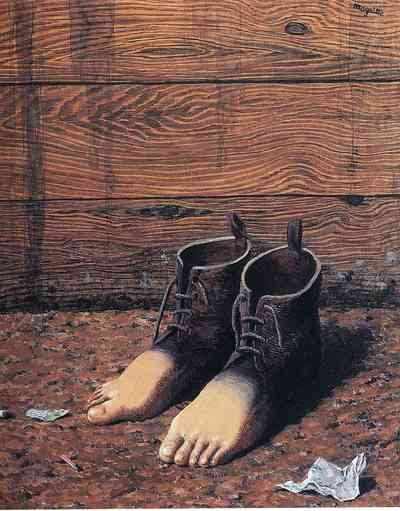

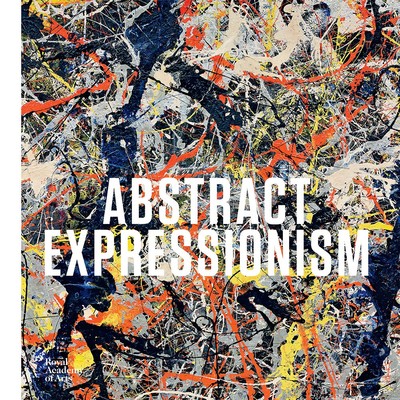

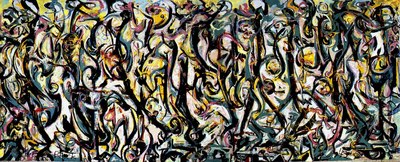

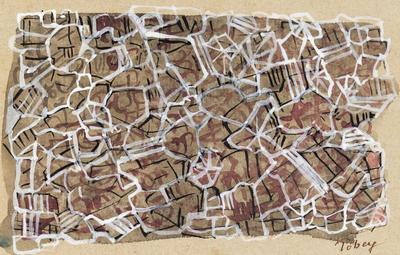

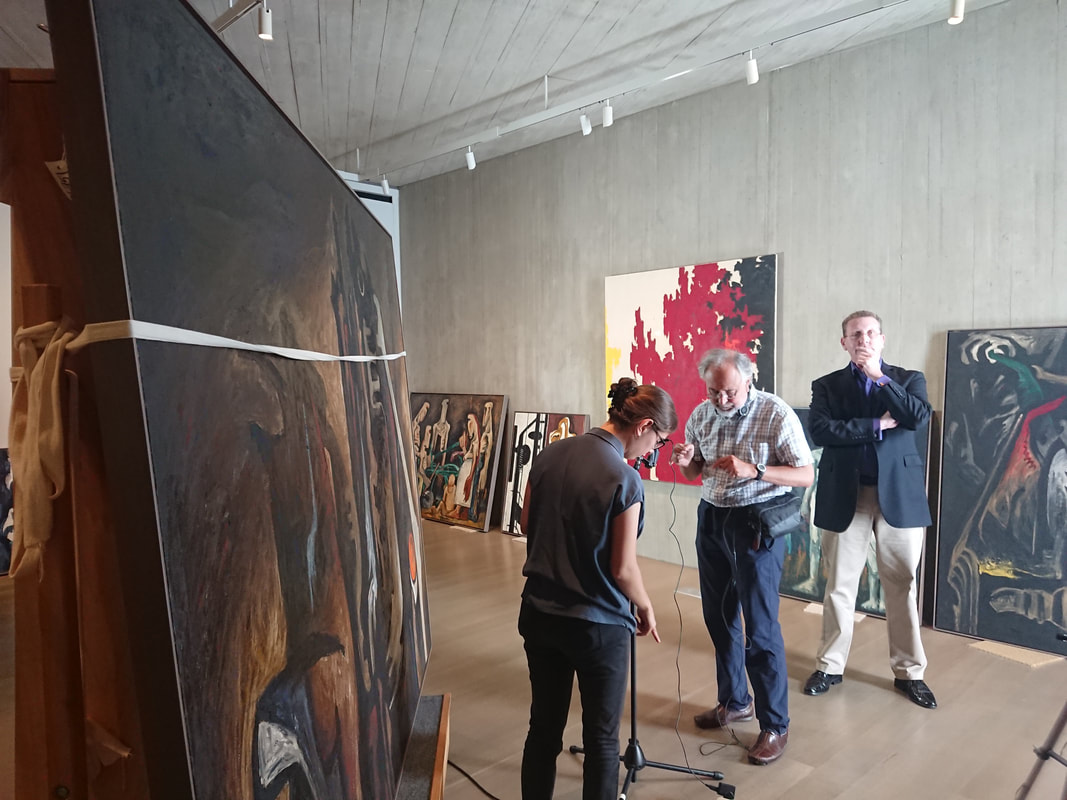

The Ashurst Emerging Artist Prize 2017 Judging Panel is a selection of highly respected and renowned individuals in the art world, who cover a wide range of viewpoints and varied tastes for all movements, mediums and types of Fine Art. We are proud to have Dr David Anfam join this year’s Judging Panel and in this blog we ask him your questions so that you can get to know him and his work, as well as gain some advice and tips on the art world.  About Dr David Anfam David is Senior Consulting Curator at the Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, and Director of its Research Center. Based in London, Anfam’s many books and catalogues over the past forty years include studies of Jackson Pollock, Edward Kienholz, Howard Hodgkin, Wayne Thiebaud, Brice Marden, Jeff Elrod, Anish Kapoor and Mark Rothko: The Works on Canvas – A Catalogue Raisonné (Yale University Press, 1998), which received the 2000 Mitchell Prize for the History Art. He is the preeminent authority on Abstract Expressionism and his exhibition Abstract Expressionism, held at the Royal Academy of Arts last year, was described by Jackie Wullschlager, Chief Art Critic at the Financial Times, as "the most pleasurable, provocative exhibition of American art in Britain this century". Q1: Tell us about your pathway into the arts. A1: My interest in art began quite early on as a child. There were two reasons: one negative, the other positive. When I was young I was often sick, especially with bronchitis that kept me in bed for a week or two at a time. Those were the days in pre-Thatcherite Britain when public libraries had serious funding – it’s hard to imagine now that was ever the case, but it was. So my parents – both of whom were not without a feeling for art – borrowed books from the local library to keep me relatively content. Two types of volumes particularly fascinated. The first was Phaidon’s Colour Library series. I loved being able to look at a full-page reproduction and read about it on the facing page. The second were the Albert Skira art books, mostly monographs and movements. Whereas Phaidon’s series was large and slender in format, Skira’s was compact and comparatively thick – they perfectly complemented each other. In a nutshell, then, the trauma of illness ultimately became a kind of muse. Being stuck in bed propelled me into the world of art. In retrospect, this now reminds me a bit of Nietzsche’s famous remark: ‘we have art so as not to die of the truth.’ Of course, I guess art has its own kind of truth, just as literature does. Consoling fictions, ideas of order and the like that life may deny us. The second reason was more benign. At school there used to be framed posters on some of the walls with reproductions and accompanying texts. Leonardo, Rembrandt, Renoir – those kind of ‘popular’ names. When we queued to go into classes – which I often hated, not least because of my deafness – I started to study these posters. The more I saw and read, the more I wanted to explore different artistic periods, styles and so on. They promised a limitless horizon beyond everyday drudgery. Actually, my deafness is not coincidental. Years later, an academic pointed out something so obvious that I had never realized it. In short, that because the world of sound was partially closed to me that of vision became the more enthralling. Another big issue that I’ve only grasped with hindsight is that, simply put, art’s magnetism was, again, twofold (I know, everything seems to come in pairs like Noah’s Ark, doesn’t it?). On the one hand and looking back, color is what gripped me from the start. On the other hand, I was always drawn to images that captured the enchantment, anxiety, strangeness or even horror of life. No wonder figures such as Bruegel, Titian, Vermeer, Cézanne, Munch, Bonnard, Rothko and Clyfford Still have long been fixed stars in my firmament, so to speak. In varying degrees, each of them struck a balance or at least a dialectic between form and content, the visual and the existential (Titian’s Flaying of Marsyas has to be the last painterly word on human suffering, a sort of testament to the belief that this is the lot of humanity). No wonder Rothko also became my idol. My father also used to take me to the local museum in Brighton, which then had on loan much of the remarkable Edward James collection before it got sold. He kept focusing us on two paintings: Magritte’s The Red Model II and an obscure English artist called Algernon Newton. The Magritte with its deathly feet turning into boots (or vice-versa) always struck us alike as scary, whereas Newton’s Paddington Basin (1925) had an almost abstract, miraculous precision to it in which the very grime of London’s air seemed to be captured like an amber that froze forever the geometrically stylized warehouses and water. Magritte’s uncanny disquiet met Newton’s canny quiescence. Somewhere in here are the roots of opposing tendencies that much later influenced my ways of seeing. So by about the age of 14 or 15 I had decided to become an art historian rather than a chemist (in chemistry lessons the diverse colors and textures – from the crystalline to the liquid, sulphur’s pungent yellow and copper sulphate’s dreamy blue captivated me). When the time came to apply for a university position, I asked an English teacher, who liked to rightly goad his pupils into achievement, what should be my number one choice? He shot back, the Courtauld Institute of Art. In the same breath he added that I’d never make it because at one level it looked like a finishing school for rich girls who told their daddies they wanted to ‘do’ art. To cut a long story short, I did get to the Courtauld with what was then its stellar faculty, where a state grant saw me through an undergraduate degree and well into a PhD too, including a year’s research in the US. John Golding was my supervisor and I remain eternally grateful to him for keeping me on track with my heroes Still and Rothko. John also taught me never to write in jargon, an injunction that subsequently the ‘new art history’ either failed to learn or deliberately defied. The result is unreadable writing. In my opinion, the larger practical lesson to these memories is that a pathway to the arts won’t materialize out of thin air. Any country that slashes funding to libraries (or their current cyber equivalents), education, museums and so on is committing cultural hara-kiri. Q2: Tell us about your recent past projects (where can we learn more about them?). A2: Over the past few years I’ve been very fortunate to be constantly engaged with energizing projects. In Denver, I’ve done a string of exhibitions at the Clyfford Still Museum. They’ve ranged from Still’s extraordinary dialogue with van Gogh and art history in general to his remarkable capacity to create works in pairs or series as well as repeating shapes within his images like replicas or doppelgängers. My long-term mission and that of the museum is to restore Still to his position as one of the titans of twentieth-century art. For those interested in learning more, the museum’s website is a pretty good starting-point. Jackson Pollock has also preoccupied me. It was exciting on several counts to do a focus exhibition around Pollock’s Mural (1943), the largest canvas he ever created. Firstly, the Getty did a terrific job of restoring this epochal painting and I’m lucky to have had the chance to study it before, during and after the massive conservation campaign. Secondly, the opening venue was the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice. There, the then-director Philip Rylands had the vision to install the works in Peggy’s palazzo itself rather than the temporary exhibition spaces - which I irreverently call 'the bottom of the garden'. This is only the second time in the Guggenheim’s history that this has happened – and to me at least the result was revelatory. Here was a potent reminder that most of the ‘big guns’ of Abstract Expressionism were, on the whole, made and shown in domestic or relatively confined spaces, not expansive ‘white cube’ galleries, which of course came later. The latter tend to dilute the works’ impact whereas in the former they come across with a hugely greater sense of concentration. Upfront rather than laid-back. Thames & Hudson published the accompanying book. If nothing else, I hope, among other things, that it clarifies Pollock’s crucial interest – and a hitherto underestimated one – in photography. A third project – perhaps the most rewarding of all – was Abstract Expressionism at the Royal Academy, which I co-curated. To my eye, the RA’s magisterial galleries are the finest in London bar none. Against all expectations we got a veritable cornucopia of loans. For example, Pollock’s newly-cleaned Mural faced off against his Blue Poles. I doubt if we will see these two pictures – effectively the alpha and omega of Pollock’s core trajectory – together again in a long time. When the RA show closed in Bilbao last June, I felt it ought to be my swansong on the subject. Which is not to say that I won’t continue with Ab Ex© – on the contrary, I feel so close to it that I’ve recently decided (don’t laugh) to copyright this abbreviation since for years I’ve found the full term to be such a mouthful when lecturing or writing – but rather that it’s key to always diversify in order not to stand still, become fossilized or intellectually archival. Speaking of which, the opportunity to write a longish essay on the late Belgian artist Philippe Vandenberg was for me another of last year’s highlights. Not being very familiar with Vandenberg’s art until then, I came to it cold, which is much better than being jaded. Thus I found it tonic to reconsider figuration against the artist’s involvement with memory, angst and the awful historical events of the past century. Hauser & Wirth did the show in New York and published the meaty catalogue. Which reminds me that commercial galleries now can be a lot more scholarly than academe. Likewise, I jumped at the offer from Blain|Southern to write about Jonas Burgert for his exhibition at Mambo, Bologna. Jonas has given representationalism a new lease of life in canvases that are often vast in scale and equally potent for their singular mix of carnivalesque brightness and darkly nightmarish enigmas. Three visits to Jonas’s Berlin studio in the last twelve months or so are reminders, if a reminder is necessary, that there’s no substitute for encountering art in the flesh and as it is being made. I can think of academics to whom such a sentiment might sound naïve. If so, let them feed on their own theories. Truth to tell, though, I do believe in theory myself – except that it should never be worn like an exoskeleton. Q3: What are you working on at the moment and over the next year? A3: Right now I have an exhibition of Larry Poons’s paintings in the twenty-first century that's just opened at the Roberto Polo Gallery in Brussels. Alongside Frank Stella (who admires him greatly) Larry is one of the two major survivors from the heroic generation of American Color Field painters of the 1960s. At eighty, Larry is painting with the vigor of a man half his age. He was also among the first to turn against Clement Greenberg’s overweening purist dogmas. In turn, hopefully this show will lead to a far larger project or two. Life is too short to engage with only the biggest ‘names’ in art, especially when quieter hands can produce work of comparable or even greater substance to the hyped stars. Consequently, I have a publication upcoming with the Ronchini Gallery on the ravishingly polished Italian abstract painter Paolo Serra who’s little known outside his country. In complete contrast, if everything goes according to plan, I will also be looking towards China for another project, which I must otherwise keep under wraps for the time being. Q4: Where did your interest in and focus on Abstract Expressionism begin? A4: The answer is simple. My father had a lifelong romance with American culture, as indeed did many people of his generation this side of the water post-1945 to whom the US looked like, well, the future. Someone told me that was how even E.H. Gombrich regarded it. That my father never crossed the Atlantic probably intensified his feelings. Thus I was brought up on a diet of Frank Sinatra, jazz, film noir, Hemingway, silk suits, Betty Crocker cake mix and big-finned cars (if memory serves, before I turned up my dad once owned a Chevy, which must have been a sight in Dulwich circa 1950). He never got quite as far as Ab Ex, though. I did. Q5: What constitutes good Abstract Expressionism? (We know it’s a big, simplistic question, but any comments would be interesting for the wide audience we have). A5: Ouch, you’re not supposed to ask such difficult questions! Seriously, at the end of the day quality comes in just one size. Whatever that is, it either hits you outright or subtly seduces. Rothko, Still and Pollock can do both. They juggle spontaneity and deliberation, rawness and refinement. With his synthesis of iron discipline, reductiveness and color that hypnotizes the gaze, Ad Reinhardt was a genius at the second approach. The show of his blue paintings at Zwirner New York last autumn threw me. So cool yet so, well, ardent. At the RA, the de Koonings, Klines and David Smiths looked as fresh and challenging as if they’d been done yesterday. The best of Ab Ex has real staying power, the lesser lights tend to feel like exponents of a period style. Then again, there’s a figure such as Richard Pousette-Dart. Like Mark Tobey and Sam Francis, Pousette-Dart is virtually unknown or at least undervalued in this country. My guess is that Francis’s big canvases at the RA went over more than a few people’s heads. At his finest, Pousette-Dart had a deeply poetic, magical vision. Maybe the ultimate test of top drawer Ab Ex is whether it can still do something for successive generations who were born after it. At the RA it was heartening to see young people – doubtless fledgling artists among them – palpably responding to what was on the walls with real enthusiasm. That’s the test of a classic: it reinvents itself over time for new eyes. Q6: Do you think your likes and dislikes, tastes in art, have changed over time? Do you have any examples? A6: Yes. I am starting to grow weary of abstraction. I’ll never forsake it but I do need periodic doses of figuration in order to sustain a healthy appetite, as it were. Once upon a time, I thought Morandi was a bore. Now I could happily see an entire museum of his work, as I did in Venice in 1998. Howard Hodgkin was a superb painter and a very nice chap too on whom I enjoyed writing. Nonetheless, I am sated with HH’s work, at least for the time being. When I was young I loved Delacroix: these days he frequently strikes me as dull. At the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam on Christmas Day I stumbled across a still life of peaches by the seventeen-century painter Adriaen Coorte that I scrutinized for almost a quarter of an hour. Years ago I’d probably never even have noticed it. Previously, I tended to like what I half-jokingly call ‘messy’ artists – from Bosch to, say, Nolde or Basquiat. ‘Control freak’ artists – Piero to Brice Marden and Agnes Martin – have increasingly if not altogether replaced them in my estimation. To cite a random name or two, at first I never much cared for Cindy Sherman or Roxy Paine, both of whom now strike me as marvelous. Ditto Barry X. Ball and others too numerous to mention. Never a favorite of Damien Hirst, I thought his extravaganza at the last Venice Biennale was a work of genius down to the mock-scholarly brochure. Q7: Do you have any advice for emerging artists? A7: It’s the lesson that Clyfford Still would have given them. Go your own way, resist the blandishments of Vanity Fair – the social phenomenon, that is, not the magazine – remember that you can never think nor look too much… and don’t despair if you don’t make it to the top ten. As Mahler said, ‘my time will come.’ Q8: Where do you think many artists falter in their practice or career? A8: Getting older and more celebrated, they repeat themselves and/or sell out.

Q10: Do you have any thoughts or predictions for the art world? (A very open, difficult question!). A10: The current overheating cannot last forever. What goes up must come down. Or must it? As wily old Karl Marx was the first to avow, capitalism – for better or worse – never ceases to amaze. Nor does art. ©.Art Ex Ltd 2018 Join our newsletter (click here) to be notified of the next issue of interviews with the judges as well as invites to our exclusive events for artists and news on the art prize.

Interview by Conrad Carvalho and Caitlin Smyth

3 Comments

Mrs Raj Thiara Takhar

25/1/2018 09:07:20

I am a soul that loves everything i see and i laugh for no reason ! but I love drawing and music . David Bowie has been my inspiration

Reply

25/1/2018 09:11:53

hi,,resp ,,nice to know about mr,Dr David Anfam ,,i am very ples to read about ,,,thanks my solo show for my paintings in newyork in this June ,,4th to 16th at one art gallery ,,27 warren st tribe ca ,,,NYC ,,thanks a lot for inform me ,,ples see my web and if you say about my work ,,ohhh i am very very glad ,,thanks ,,pranav shah ,,,,

Reply

Абдулов Равиль Султанович

25/1/2018 15:33:07

Как все похоже на мою художественную жизнь дошел до абстрактно конструктивной живописи ,но возвращаюсь к фигуративности ...

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Oaktree & Tiger TeamArt experts giving advice to emerging artists to build their careers and find success. Organisers of the Ashurst Emerging Artist Prize 2020, artist agent and art consultants. Archives

December 2019

Categories

All

|

|

Ashurst Emerging Artist Prize 2021

Address: Ashurst, London Fruit & Wool Exchange, Duval Square, London E1 6PW, UK Email: [email protected] Website: www.artprize.co.uk Managed by Oaktree & Tiger |

|

Subscribe to receive updates and invites...

© 2014 - 2021 All Rights Reserved

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed